Hello cool friends! This is not my intended update for the month. I have been working on a much longer 2-part series about comics. Part 1 covers how I discovered comics as a teenager the way that my friends discovered punk and emo music. Part 2 covers the eventual existential crisis that came when I finally got a copy of Cages by Dave McKean as an adult. It has been slow going due to a number of project deadlines coming up in July. I feel like I blinked and I am suddenly nearing the end of June without making a single post.

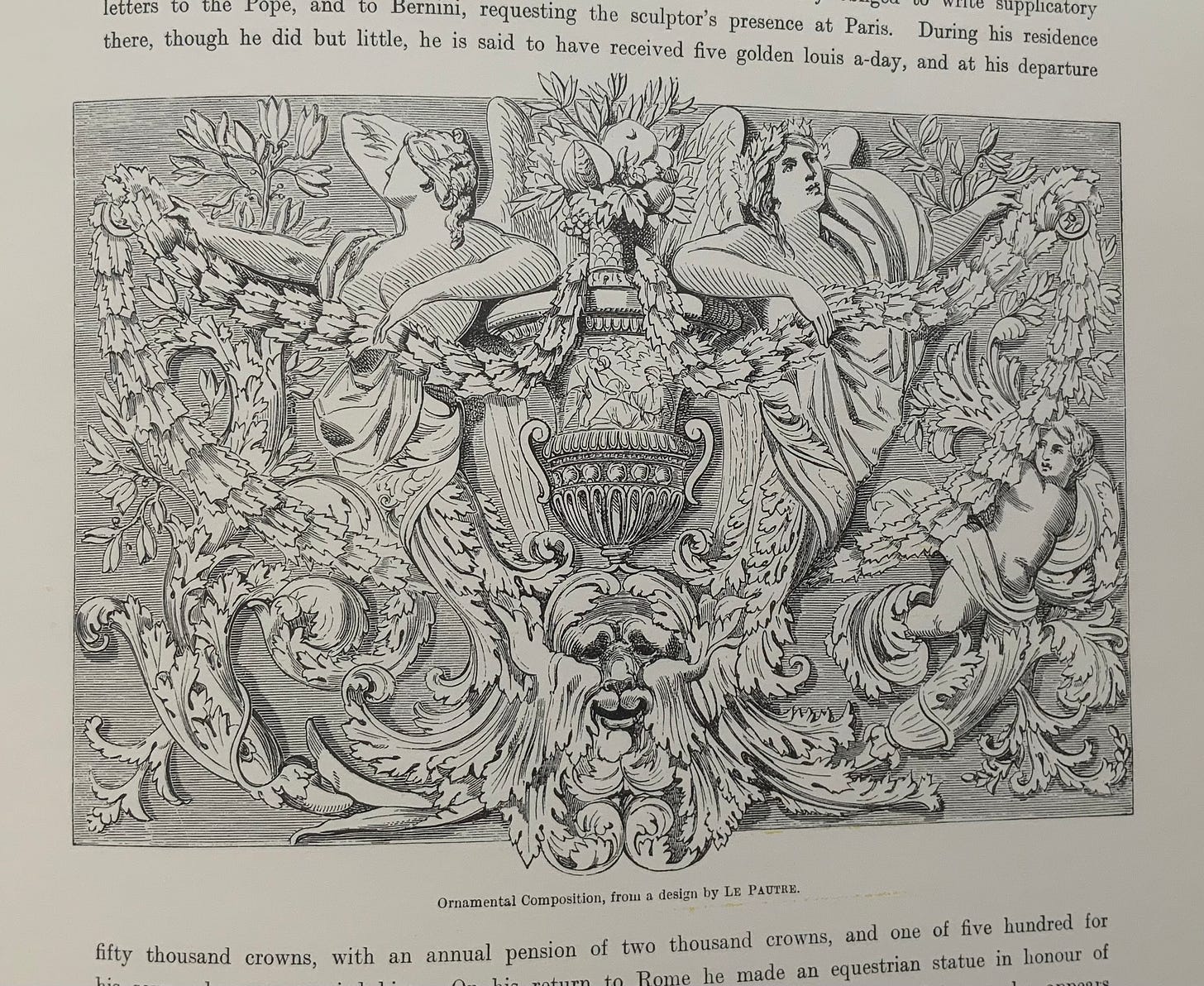

One of my current projects is a book cover and layout for April Gloaming Press for a beautifully unconventional book of poems called The Wingtip Prophecy. It is a dense book evoking images of Roman augurs and southern farmers. When imagining the book itself, I imagine it streaked by hands covered in black earth, and I cannot tell if those hands were planting or burying. So how do I go about making a cover like that? Well, I’ve decided to base it on an old almanac!

I started the project like I do most projects by googling a lot for reference images. I’ve been looking at archives of various agriculture almanacs from the 18th, 19th, and turn of the 20th century. I have found some truly beautiful images. But I kept running into the same problem: How do I evoke the image of an almanac without wholesale copying an old design? I’m not very familiar with drawing in this style, so I don’t have the knowledge or muscle memory to truly invent my own forms on a deadline. Enter The Grammar of Ornament!

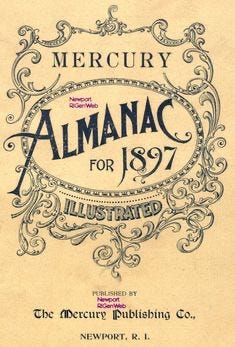

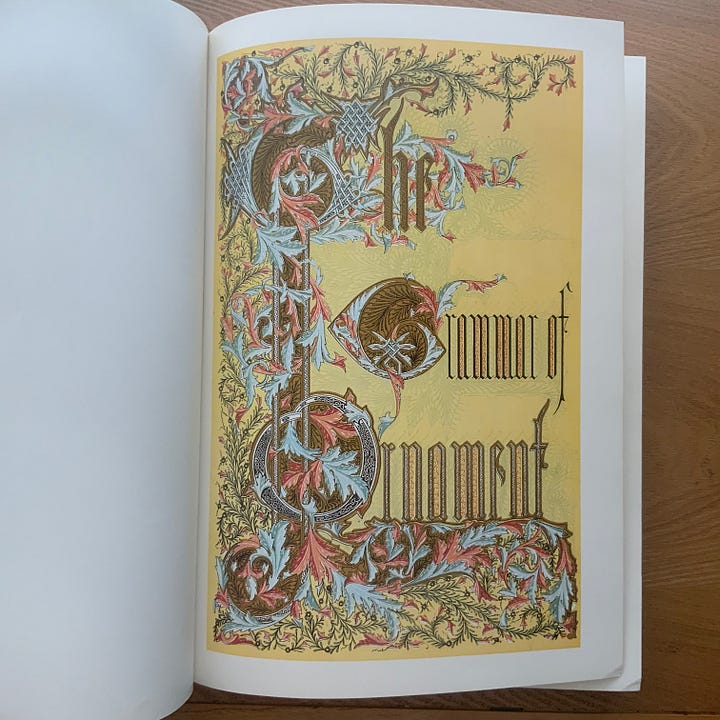

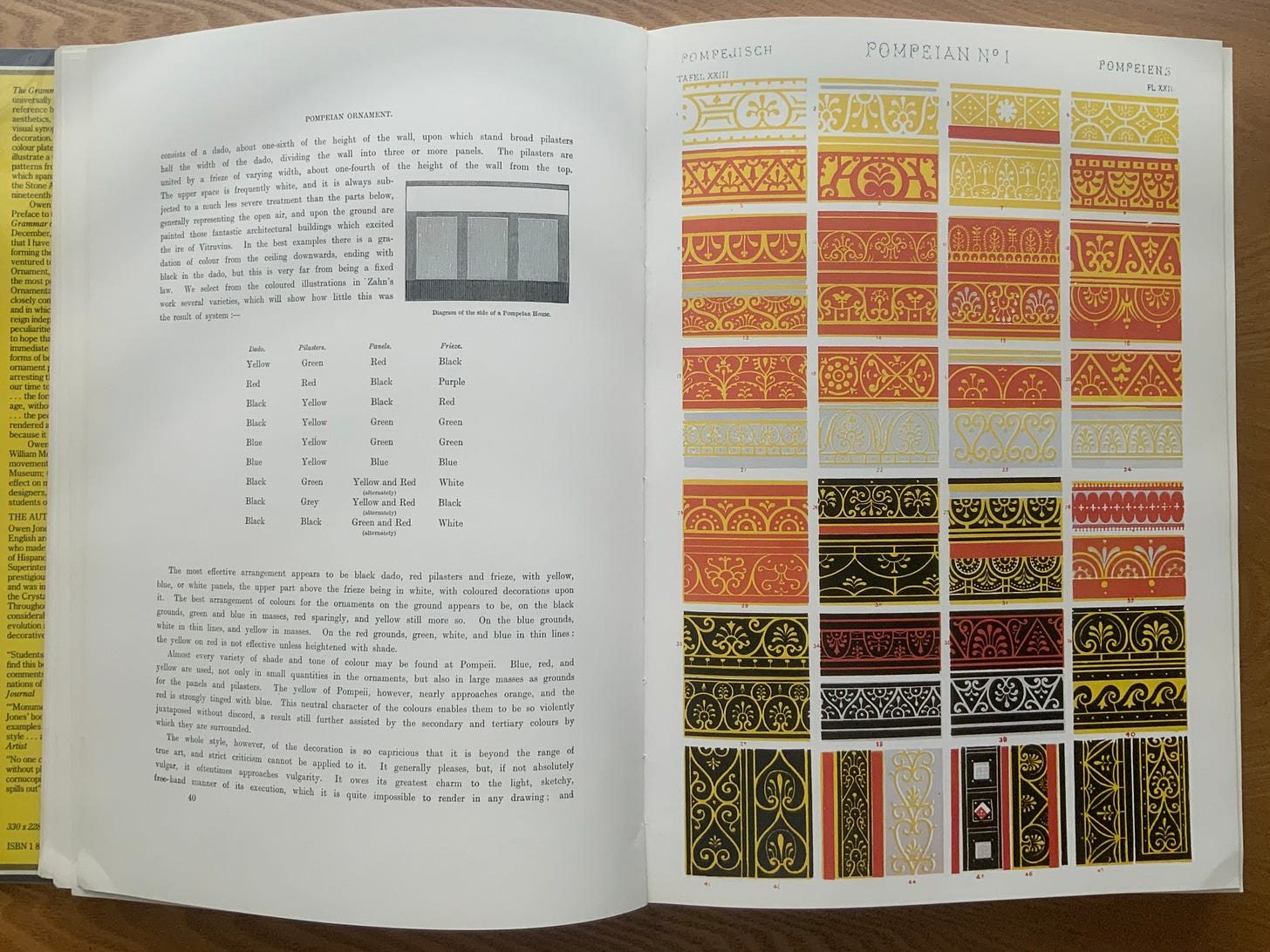

The Grammar of Ornament is a 19th century reference guide for designers. It contains illustrated plates of historical decorative motifs from all over the world. My wonderful partner heard about it on an episode of 99% Invisible and bought me a copy for Christmas several years ago. If you want to read more about its origin and legacy, I found this article from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

For this project, I am focusing primarily on Greek, Roman, and “Pompeian” motifs because the poetry often references Roman augurs and these motifs seem to be what are most referenced in later almanac design. This is my first time using The Grammar of Ornament so extensively for reference. This is also my first time actually reading the text. One of my favorite things is discovering other peoples’ strong opinions about niche subjects. I did not expect the author, Owen Jones, to have so many of these Opinions™. Listen to this:

“The real greatness of the Romans is rather to be seen in their palaces, baths, theaters, aqueducts, and other works of public utility, than in their temple architecture, which being the expression of a religion borrowed from the Greeks, and in which probably they had little faith, exhibits a corresponding want of earnestness and art-worship.”

Shots fired, Mr. Jones.

And when talking about Pompeii:

“The whole style, however, of the decoration is so capricious that it is beyond the range of true art, and strict criticism cannot be applied to it. It generally pleases, but, if not absolutely vulgar, it oftentimes approaches vulgarity.”

I expected a text from 1856 to have problematic things to say about non-western decorative arts. I went to art school and learned about everyone from the Renaissance to Modernists’ thoughts about “primitive” art. But I don’t recall reading anyone throw such shade at the Romans. The whole text oozes pretentiousness under the guise of expertise and, on first read, I couldn’t help but respect the audacity. There is something that seems almost quixotic about this lone Victorian architect making such sweeping judgements about the artisans of an entire imperial civilization.

But that’s just my interpretation. I studied art history more than 150 years after this text was written. I couldn’t help but wonder if terms like “vulgarity” and “want of earnestness” might have been less loaded in context? I asked noted historian and father Dr. Timothy Hall for a historical perspective.

He said:

“You ever hear the Deep Purple song with the line, “I’ve got an English brain that’s gonna make me wise?” This is definitely cut from the same cloth. The Victorians were truly insufferable in their arrogance, with no right to be so given their blundering butchery and plunder of archaeological sites.

These quotations I’m sure are intended as serious judgments on Roman art and design. You can just imagine a room full of cigar-smoking gents at a lecture nodding knowingly. But good grief, just go to the Vatican and look at all those classical sculptures. The Greeks were great sculptors, no doubt, but some of those Roman sculptures are every bit as lifelike, as if the white witch [from C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe] touched them with her wand in the very middle of some dramatic action.

Jones was referring mostly to decorative ornamentation rather than figural sculpting ability, but I think this judgment still stands. I can’t help but wonder what Owen Jones would say about our knowledge that Ancient Greek friezes were painted. Would he think that this, too, was “vulgar” like Pompeii, as many modern classicists do? Whence comes his standard for evaluating “the range of true art”?

It seems that Jones was being every bit as arrogant and audacious as I suspected, but without the self-awareness that often comes with the modern practice of shade throwing. Thinking about this work in context, Jones’ words are still hilarious to me. However, he wasn’t really an underdog. His ideas are reflective of a larger culture that did real damage to the historical record and living human people and cultures that echoes down to this day. Alas, so much evil in the world stems from the laughable arrogance of “cigar smoking gents.”

Jones has been dead for a long time, but both his work and his influence persist to this day. I know the popular phrase begins “it is better to die a hero…” but the thing about achieving this type of “immortality” is that this half-life can persist long enough to become the villain. Or to at least be trashed by an unknown blogger and their dad on the internet. I think Owen Jones deserves it after what he said about the entire civilization of Pompeii and others. For myself, I can only hope I am remembered long enough to be sardonically trashed for my shortcomings when I can no longer grow or defend myself.

Still, for all its shortcomings, The Grammar of Ornament is a fantastic reference book. I am grateful for the way Owen Jones organized and compiled it and paved the way for designers to come. Its dumb opinions are a product of its time in a way that feels like a feature rather than a bug. If you want to take a look at it yourself, it is available on The Internet Archive’s Open Library. If you like what you see, it is once again in print and available for purchase from Princeton University Press. This is one of those reference books that you really need to hold in your hands for the full effect. Might I recommend you special order it from your nearest independent bookstore? Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have an almanac-inspired book cover to finish, among other things.

Stay Cool!

–Theo